2. “Territorial Waters”

If Türkiye ever goes to war with Grece, it will have political objectives.

First of all, it is not called the “International Maritime Law.” Its correct name is the “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)”.

This is a “convention”, meaning only signatory states are bound by it.

Non-signatories have no obligations under it.

If two states—one a signatory and one not—have a maritime dispute, the convention does not automatically apply.

Such disputes are resolved through “negotiations and mutual agreement”.

If no resolution is reached, parties “may” bring the case to international courts—but this is “not mandatory”.

A fundamental principle is that “disputes should not be resolved by force”.

However, by 2025, this principle holds little weight in practice.

Consequently, nations involved in international disputes—especially those confident in their strength—increasingly rely on “military deterrence”.

These objectives must be to address the issues I've outlined below.

► --

“The Core Issue: Turkish-Greek Disputes”

The most contentious border is the “maritime boundary”, with key problems:

1. “Continental Shelf Dispute”:

► Geographically, the Aegean is mostly shallower than 200m, meaning many Greek islands sit on Turkey’s continental shelf.

► Under UNCLOS, if states are closer than 200 nautical miles, a “median line” applies—but Greece rejects this.

2.

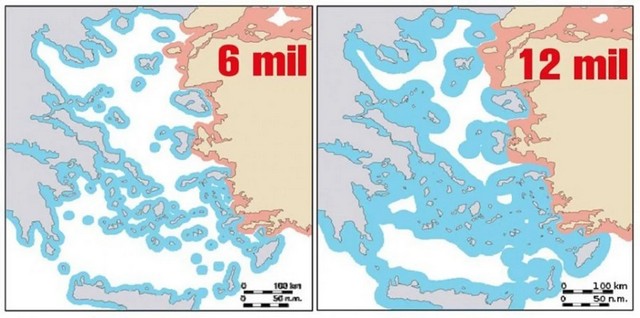

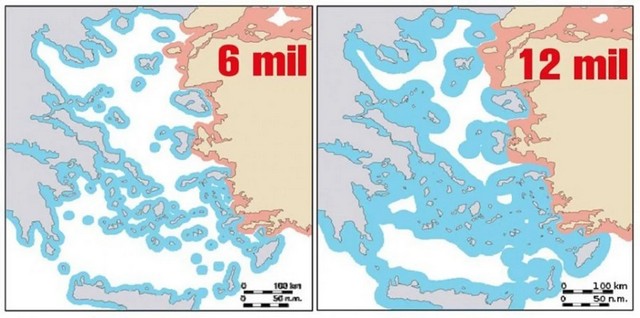

“Territorial Waters”

3. “Airspace Violations”

4. “Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Claims”

5. “Search-and-Rescue Jurisdiction Conflicts”

6. “Unclear Sovereignty Over Islets”

Globally, disputes over “adjacent islands” or “those on another state’s shelf” are common.

Solutions include:

► “Negotiations”

► “International arbitration”

► “Delaying resolution”

► “Military force”

7. “Militarization of Demilitarized Islands”:

Greece’s arming of islands like Lesbos and Samos violates treaties, undermining trust.

If Greece disregards past agreements, why trust future ones?

8. “The problem of violation of basic human rights of the Turks of Western Thrace”